I wanted to discuss a term that I found memorable recently: ground truth. It resonated with me when I first heard it, as I’m routinely in discussions where we are articulating technical problems and how we plan to solve them. This act of describing the problem to an audience with varying levels of understanding can be challenging. We often have limited time in how we bring people to shared understanding. This restricts our ability to sufficiently describe all the history and contributing factors of that problem. By having a close understanding to what is occurring, the better we can articulate this understanding with others. In this post, I will dig into the term “ground truth” and some considerations in the words we use when sharing this understanding.

The Term#

When digging into a problem, we seek to have a clear understanding of the environment. We collect information from our trusted sources. The shorter the distance that information travels when we receive it, the stronger its perceived value. For example, “seeing it with your own eyes” is a highly influential experience with information. However, there is a cost in getting close to these raw information sources. You can’t be everywhere at once or process all these lower-level representations of data. This cost can be reduced when we rely on secondary sources that provide reports or transformed representations of that information. This is helpful; however, it can disconnect us from what is truly happening. It may only tell part of the story.

I recently finished Colin Powel’s book, It Worked for Me, which introduced the term ground truth. In his book, he repeatedly refers to the term “ground truth.” In one chapter, he shares how he develops ways of getting to know what’s happening. Here is a small segment:

The more senior you become, the more staff you have to protect you from yourself and to push their own agenda. They mean well, but they can insulate you from ground truth. You have to get out and walk the floor. Have trusted agents and friends call you when they think the emperor has no clothes. In the Army, chaplains, inspectors general, and sergeants major can always give you a ground truth perspective. Above all, never forget you were ground truth once.

In my experience, I have seen leaders do this effectively where they utilize trusted sources of information which are close to what is occurring. However, they do not solely rely on this, but rather build a routine of connecting directly to the “ground level.” This might be directly talking with customers or joining different team sessions without notice to just listen in on what is occurring. With software development, the cultural philosophy of DevOps enables this by having team members well connected to the operational aspects of their software. It minimizes team members hearing second or third hand information of what is working or not; but rather participating in these very occurrences which builds an acute understanding.

Getting to Ground Truth#

It is expensive to be well connected with ground truth, as this can take more time to maintain this connection. This is especially true as you grow in your career and have more scope. Though, that doesn’t mean it can’t be achievable. Sampling across groups and finding a routine which allows you to stay connected can keep you fresh on these perspectives. That routine could look like skip-level meetings every week for managers. Another example is having senior engineers participating in production post-incident analysis, where they can hear and learn from direct experiences of those close to the issue.

Maintaining a ground truth perspective requires ongoing effort. In my mind, it is like we are in a low gravity environment, which requires continuous work to maintain a close connection to the ground. These close connections can be relationships to others or observing the environment first-hand. The point being, if you are not working to get close to the ground level source, you will naturally separate from it.

Hazards in Sharing our Understanding#

When we gain this ground truth understanding, we want to share it with others! In this next section, I wanted to describe two types of words that warrant your awareness: absolutes and weasel words. These linguistic hazards can deteriorate our messaging and result in a degraded perception by others. My goal is to briefly share the awareness of these words and their impact, so we can improve our messaging without falling into these traps.

Avoid Absolutes#

When we observe that something happens 0% or 100% of the time, it seems reasonable to use the words like “never” or “always” when sharing the observation. However, these absolute words can quickly detract people when we communicate our observations. When we state “we always do X,” it only takes one exception from a listener to debunk that understanding. Furthermore, it can derail your entire flow of communication, as people get distracted by that absolute statement as they are recalling examples which contradict it. This can lead people to believe you have a false or limited understanding since you weren’t aware of these contradictions.

If you are communicating observations of a system, avoid using absolutes. It is easy for them to enter our vocabulary when trying to emphasize a point. However, they often do more damage than good when communicating your ground truth perspective.

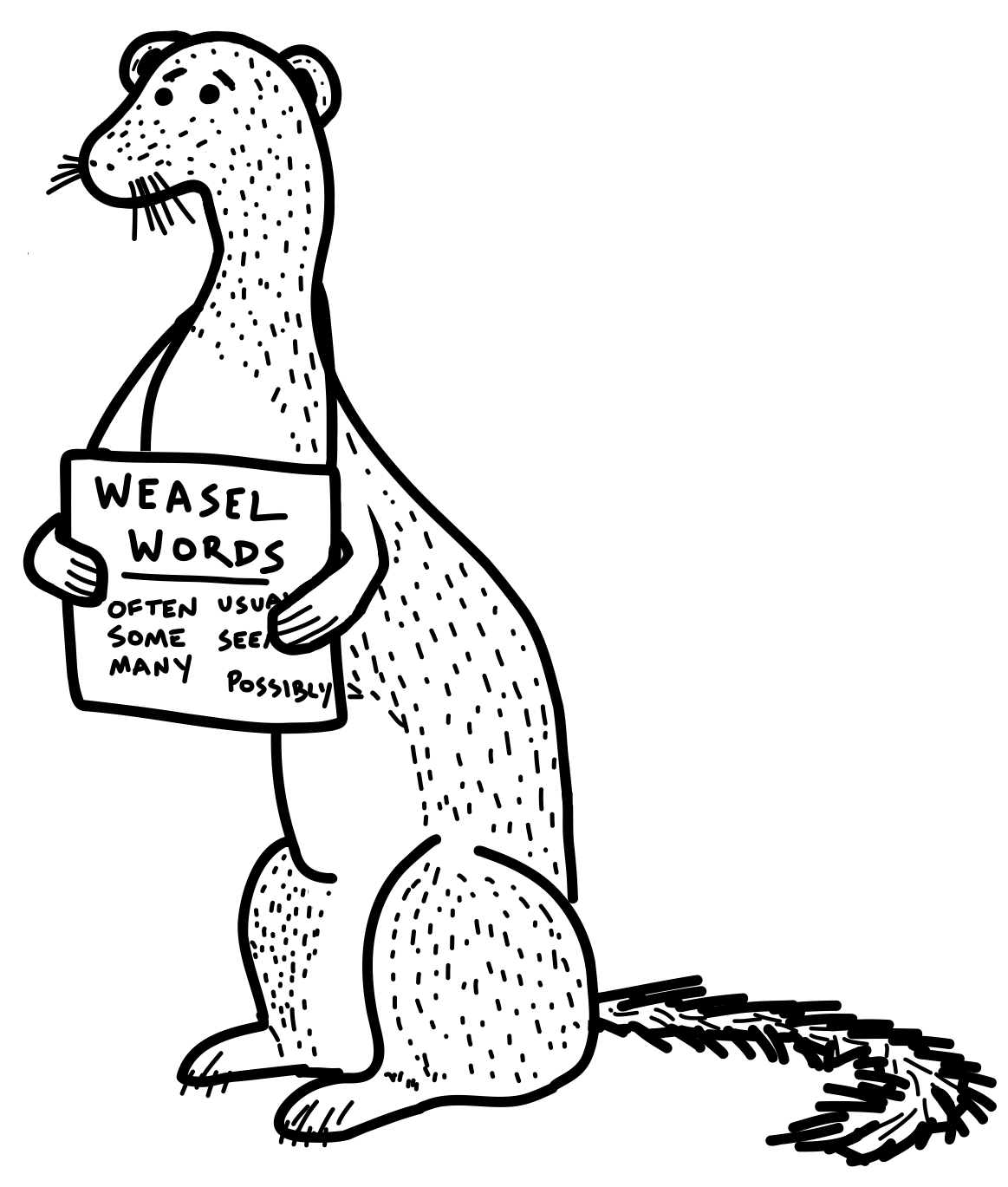

Beware of Weasel Words#

When avoiding the use of absolutes, another trap we may encounter is around ambiguous descriptions of our observations. These phrases can be known as weasel words, which are “a word that has little meaning, or more than one meaning, that you use when you want to avoid saying something in a clear or direct way” (definition). Examples of this can be adverbs like “often” or “sometimes.” When avoiding absolutes in sharing our perspective, generalization can occur by the use of quantifiers. To an audience who is aware of a situation, using quantifiers like “some” or “many” can feel misleading. While you may not be intending to be vague or misleading in the usage of these words, your audience may see it differently. Which again, can distract them from the main things you are wanting to share.

You may be wondering, “What words can I use?” Use quantifiable measures in your description with context of how it was captured. Rather than having “the services are always slow to start-up,” or “most services have a slow start-up time,” you can state “65% of services have a start-up time over 30 seconds when we sampled the past two weeks of deployments.” By including quantifiable measures, including the context of when and how you captured it, you quickly share your direct and clear perspective to others.

With this advice, don’t feel compelled to state everything paired with numerical stats. That isn’t the point. The point is to be direct and specific when possible. When we state “slow,” it may be unclear how slow that is (10 seconds, 15 seconds, 1 minute). Also, it is natural to use generalization first before we break down into specifics. If you use a quantifier like “most,” immediately follow-up with something like “by most, I mean more than half.” While “more than half” isn’t that specific, it does communicate how you understand it, which may be an imprecise stage of understanding. That’s much better than leaving it to the audience to determine that precision.

Conclusion#

This isn’t easy. It takes time, patience, and discipline in maintaining a ground truth perspective. Beyond the knowledge you gain, it can expand your personal network with those possesing a close perspective and improves our empathy of the situation. It also takes practice and a conscious effort in the words we use when sharing our understanding to ensure it is effectively conveyed. If you catch yourself using an absolute or a generalized measure, work on following up with what you mean by its usage.

Stay curious, and keep finding ways to connect with your ground truth!